I'm an NPC and So are You

TikTok's NPC Trend is Not Extreme Capitalism. It's Business as Usual.

I’m transcribing Pinkydoll’s TikTok in the library of MOLI, Dublin’s Museum of Literature on a wet Thursday morning. My desk faces a bookcase full of upscale editions of Ulysses and Finnegan’s Wake. What at first feels incongruous takes on its own poetry:

“And then I asked him with my eyes are you ready to POW yes yes yes that was ice cream so good and his heart was going like ganggang and yes I said yes yes yes oh thank you Joel I love you.”

Pinkydoll, whose real name is Fedha Sinon, is head-to-toe in Barbiecore, a peachy velour two-piece cut low in front. Her hair is blonde and poker straight, falling down her back in stark contrast to her smooth dark skin. She holds a pink hair straightener in her left hand. A bowl of popcorn kernels sits on the table before her, and every once in a while she plucks one out with one long acrylic, placing it on the ceramic plates, letting it cook in the heat. (Really it’s miraculous that this is maybe the tenth strangest thing about the entire stream). Viewers are sending her virtual gifts. These register as animated reactions on the screen - roses, cowboy hats, cats, ducks, balloons - and she responds. There’s a gesture and a catchphrase to match each offering. ‘Hee haw you got me feeling like a cow girl’ while waving an imaginary lasso acknowledges the virtual gift of a cowboy hat, while yes yes yes, acknowledges the gift of a virtual rose. Viewers can convert money into TikTok coins, which can be used to buy virtual gifts and streamers like Pinkydoll can receive the gifts and cash them out into real money once they reach a threshold of $100, with TikTok taking a 50% cut in between. Large donations are usually acknowledged by name ‘Thank you Joel’.

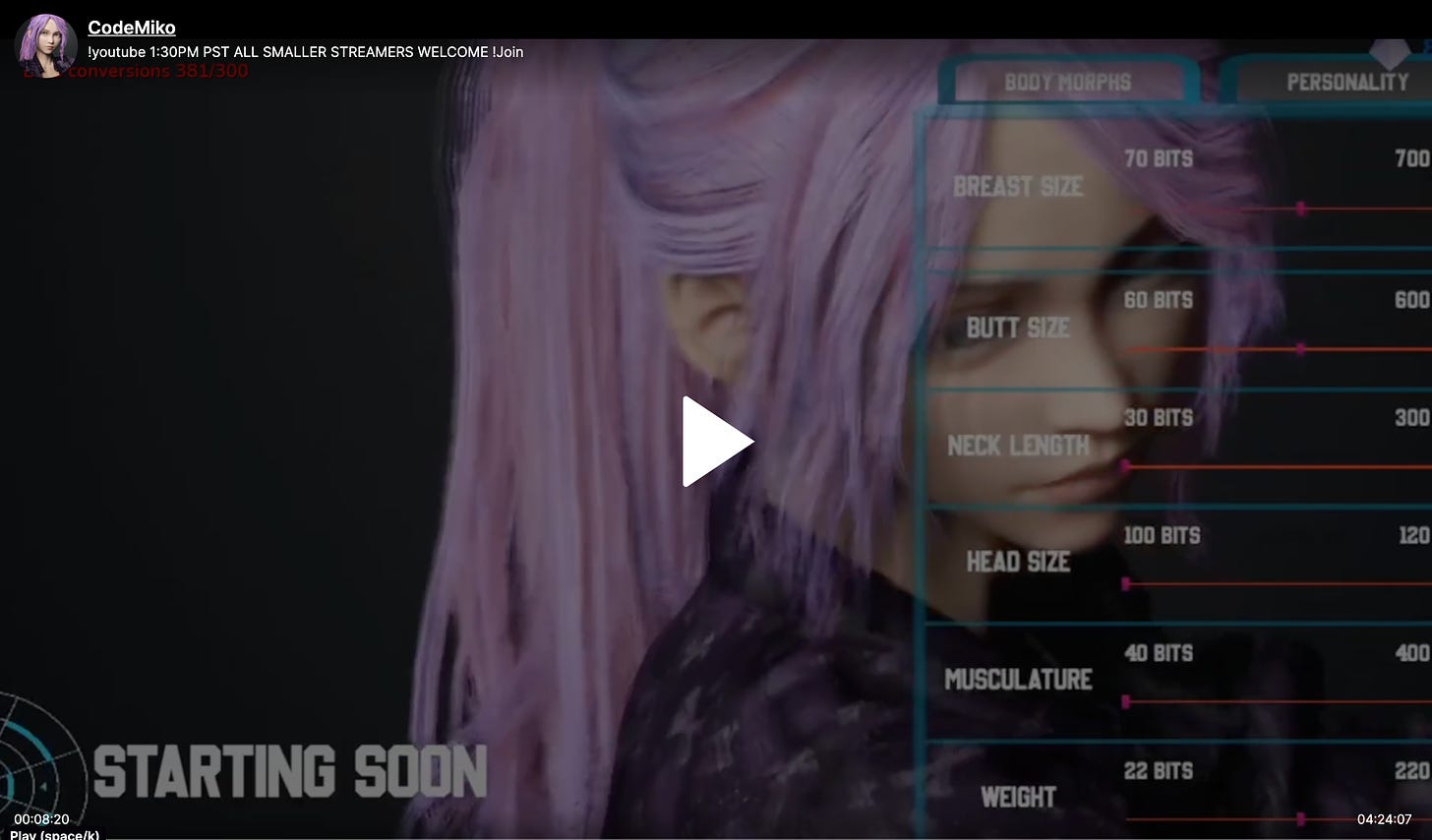

Virtual tokens and gifting is not a new phenomenon. On the Amazon-owned streaming platform Twitch, fans use virtual tokens (called Bits) to gift streamers they like. A viewer can buy these virtual tokens in the same way they might buy coins in a video game. And like in-game currencies, these tokens allow the viewer to interact in the stream, to send messages or gifts or animated emotes, to participate in games or shape content. For Amouranth, a popular ASMR streamer, 2,000 Bits will see her don a horse’s head mask and trot around the set, astride a sweeping brush. For CodeMiko, one of the site’s most popular virtual streamers, the viewers’ Bits can alter her appearance, adding or removing hair or altering breast size.

Virtual gifting has had a place on gaming and streaming platforms for some time, particularly in China. Tokens are bought with real money using a real credit card, but for fans, they feel less like real money and more like….what exactly? Not quite payments, not bribes, but maybe tips or gifts, something to say thanks, something with strings attached. These gifts can be a way to say ‘well done’ or ‘keep going’ or simply to control what happens next. Studies as to why users send these tokens come down to what sociologists call the parasocial– a sense of attachment to someone we only know online. The act of gifting as opposed to outright paying and hearing that gift acknowledged by the object of our affection reinforces a feeling of real connection. And it’s addictive. People will pay a lot of money to feel like they are connected to Pinkydoll. Sinon has told the New York Times that she makes up to $3000 in one live session.

Pinkydoll is one of a number of TikTok live streamers who have eked out a niche by pretending to be NPCs or non-playable characters. In keeping with the streams origins in gamer culture, NPCs are non-playable characters in video games. They can’t be controlled by other players. They have limited intelligence and a set repertoire of programmed behaviours and catchphrases (a vendor in World of Warcraft for example might say “everything has a price” and “your gold is welcome here”, while a Zelda II NPC said only “I am error”. Some are there to guide game play and narrative and others are more like street furniture, the ludic version of scene extras, chatbots and virtual assistants.

On TikTok itself the responses are supportive, but in the five days it takes for strange memes to percolate onto Instagram and the rest of the internet, the mood shifts. Many viewers are baffled and confused. Some even seem offended. I’ll sidestep the endless Black Mirror references in the comments and say the reaction is like we’re in the Hunger Games and Pinkydoll is the latest entertainer in the Capitol. Here is a performance so thoroughly monetised and debased and dehumanised that some people feel sick for watching it, and sick of the viral culture that pushed it to the top of their newsfeed. “It is absolutely Orwellian that people are making millions a year by creating brain cell-killing content like that” writes one outraged viewer, directly beneath "Idk what's worst, people who do this kinda lives [sic] or people who spend money to send gifts to this shit [skull emoji]" and “"Okay fine I guess I support the TikTok ban now". Others see it as a broader symptom of our alienation under capitalism – ‘ Why is no one on here talking about how we're forced to find ways to monetize our own existence to survive?” reads one comment by downbad.comrade and close by, “Looks like another way to dehumanize people for the sake of entertainment. Another disturbing social media trend smh.” Reactions range from dismissing the phenomenon as Gen Z culture at its weirdest or pointing and screaming ‘it late capitalism!’, but I can’t help but feel that we are missing the bigger picture, which is that we are already NPCs.

When I was a first year in art college, my lecturer showed us a clip from Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times. Chaplin gets so absorbed by twisting screws on the production line that he starts turning screws on everything. He turns, in effect, into a robot. In one scene that wouldn’t fly today he chases a matronly woman down the street, determined to screw the buttons placed at nipple level on her skirt suit. Taylorism makes bots of us all, Chaplin implies, a cog in the machine. How we laughed. And then we went to the quadrangle to get stoned. That summer, I worked in retail. I folded sweaters 9 – 5 in the large Dunnes Stores on Stephens Green, Ireland’s low-brow answer to Marks and Spencers. Then I went home and folded jumpers in my sleep. After a few weeks I graduated to the tills. Sometimes customers were rude to me. Of course they were. I was an NPC. Sometimes the repetition of each sale would make me glitch. ‘Do you have a loyalty card?’ I would ask the woman across from me. ‘Would you like a bag?’ And then a few seconds later ‘would you like a bag?... oh I’m sorry, I just asked you that’. ‘Thank you. Next please.’ Low-paid jobs make NPCs of us all. Today I have the luxury of showing my own students Modern Times, of writing about strange cultural phenomena from the other side of Stephens Green.

Pinkydoll’s robotic glitchy performance with a smile is exceptional multi-tasking. It’s maybe even exceptional performance art. But is it exceptional capitalism? No. It’s business as usual.

This said, we do need to look closer at the dynamics of the online token economy. Platforms are issuing new kinds of money-like things. Twitch Bits. TikTok coins and Gifts. Chaturbate Tokens. These tokens, which are not quite money, are popular with fans. They can be memes. They can be gamified. They feel more playful and cute than a regular transaction. But for platforms, tokens are also a regulatory sleight of hand, a way of acting as employer and bank without officially being either. Between the moment that real money is turned into a token on TikTok and cashed out again, a split occurs. TikTok takes a 50% cut before a performer like Pinkydoll can cash them out into anything that pays the rent. While enthusiastic viewers can purchase these virtual tokens and gifts with any major credit card, streamers on the platforms often struggle to cash them out on the other side. After TikTok has taken a 50% cut of the gift’s value, streamers can only be paid in cheques or lengthy ETFs and then only if their earnings exceed a certain threshold (on TikTok this is $100). Here, platforms are not just holding stations or processors, because the payment is articulated differently at either end, a situation that Antonia Hernandez, a researcher who has diagrammed the distribution of tokens on Chaturbate, describes as the ‘digital gentrification’ of the Internet.

Couched between think pieces on the singularity and Chat GPT, it’s hard not to view the TikTok NPC craze in the context of anxieties about AI and the future of work, or what we humans think of as work at any rate. Where once these anxieties mostly concerned the automation of low-skilled, menial work such as that seen in Chaplin’s Modern Times, Chat GPT and Dall-E’s performances have more recently raised the spectre of an automation of creative content. On Instagram, the racially ambiguous virtual influencer LilMiquela is affiliated with brands such as Prada and Calvin Klein. On Twitch and Chaturbate, Project Melody, a pornographic hentai model out earns her flesh and blood cohorts in virtual tips and yet embodies none of the privacy risks or stresses of exposing your life and body to the internet. More and more of these jobs will be taken by artificial intelligence, whether that’s the NPCs of virtual chatbots and assistants, or the inventive dreams of new language models. No more demeaning work for you and me. Maybe no more jobs at all. Maybe a universal basic income (although many will find this idea a lot more provocative than what Pinkydoll is doing). So what’s left but to steal the work of a robot?