When I was nineteen I gave a man I’d just met at a house party oral sex in exchange for a lift to work the following day. The terms of this exchange were never stated in any explicit fashion, but those were the terms as I understood it. It was no great hardship. He was attractive. He had a car. He was maybe two years older than I was but seemed younger, unthreatening. In fact, like bees and mice, I’m pretty sure this particular young man was more afraid of me than I was of him and the slightly business-like way I handled his penis: ‘oh well, would you look at that, Diarmuid, you’re circumcised. I’d say that’s not particular common for a hurler from Kells, would you agree?’. The following morning, after a few hours’ sleep in his narrow single bed, he gave me a lift to my job in the bookshop. That’s the funny thing about sexual negotiations. Through my teens and early twenties I had sex when I wanted to, but also occasionally when I didn’t entirely: to be polite, or because in some way I felt that some form of sex was outstanding on my balance: to pay for drinks that I hadn’t asked for, or to say thank you for a lift to a house party and even once because the cost of a taxi across the city at 2 in the morning if I turned them out into the frigid night seemed extortionate. If the tally had been explicit – two double vodkas and the cost of a taxi = oral sex, I would have been sure that I was worth more – no – sure I was not the kind of woman who would enter into such an exchange. If someone had offered me a month’s rent outright for sex I would have refused on principle, while also knowing somewhere that I’d exchanged sex for far less, in situations like this, to be polite, to not make a fuss, to not be a bore. But this is not one of those essays where the author wonders why she was so bad at saying no to sex she didn’t really want to have. All romantic and sexual relationships are composed of such unspoken tallies. And if my story is uncomfortable, it’s only because the terms of this transaction are clearly stated.

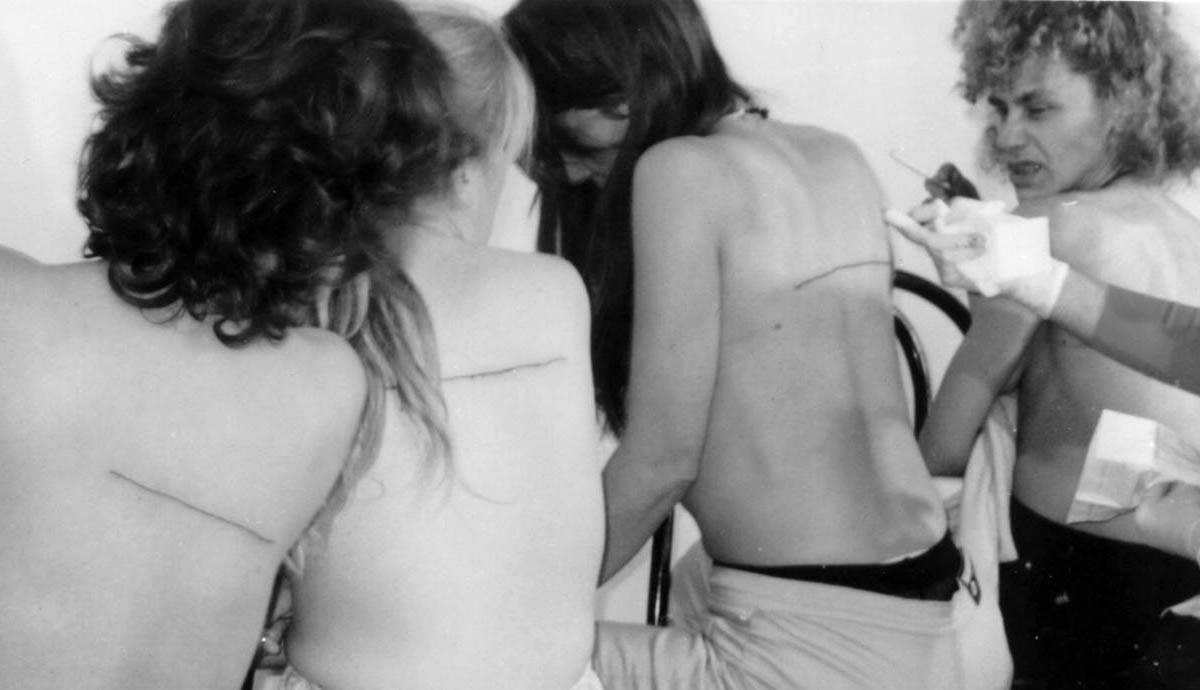

In December 2000, the artist Santiago Sierra paid four sex workers the market rate for a hit of heroin to have a line tattooed across their backs. In classic thinking, the work is distressing because it mixes money with bodily autonomy – even slavery; Sierra made visible the kinds of ‘desperate exchanges’ often found in situations of addiction or extreme economic destitution. Is it okay to buy something when the person selling it is so desperate they don’t really have what can be called a choice? Most people find Sierra’s work disturbing because the money -about $67 at the time - and the good for exchange – the permanent violation of another person’s body - don’t match. Or maybe it’s that they match a bit too well; the work shows the everyday exchanges we would rather not see. We see the desperate exchange when we would rather not see it quite so clearly. The thin line, scored over thin shoulder blades. As artworks go, I find Sierra’s work morally indefensible but also ethically fascinating – probably one of the more twisted combinations you can find in an aesthetic practice. But when I look at the photo documenting the event, showing the four women, naked from the waist up, wincing in pain or the anticipation of it, I can’t stop thinking about these questions. What kinds of transactions are acceptable? Why is it okay to commodify some things but not others? Who can afford to walk away or say no? And where do we draw the line?

In classic economic philosophy, markets and intimacy are not supposed to mix – ever. The economic anthropologist Viviana Zelizer calls this line of thinking ‘hostile worlds’. From this perspective, markets corrupt intimate life because they put a price to what should not be for sale.[i] This is why the sociologist George Simmel objected to sex work and why others reject the idea of money for surrogacy or paying for the right to pick your children up a little late from crêche.[ii] While ‘market think’ argues that goods are valued more when they are given a price, other entities, because they are not supposed to be for sale at all, are cheapened by the merest hint of a transaction.

By focusing on money as purely a market phenomenon, Zelizer argues, we fail to grasp money as a social medium. Instead, when we look more closely, all intimate connections contain some form of calculation. Zelizer points to all the ways in which things that aren’t really meant to be for sale are trucked: engagement rings for brides to be, complex treat economies for courting couples, give and take between friends, no prices and no money but still an unsaid grasp on what is owed. There is acceptable and then there is unacceptable commodification. Or maybe it’s more accurate to say that what passes and doesn’t comes down to how explicit this commodification is. If Sierra had given the women a gift of the heroin instead, would that have been more or less okay? How about a food voucher, or accommodation, or a sum of money that didn’t tally so explicitly with their drug habit? I’m not sure.

Wish Lists

As part of my research for TOKENS, I looked at the gift economies in online platforms like Twitch, Chaturbate and Only Fans. If economic anthropologists like Zelizer explored how courting couples and married women in the 20th century drew lines between gifts and payment, working hard to turn cold, hard transactions into something more like romance, was something similar happening on these platforms? How were streamers and cam models using online tokens and gifts to make transactions into something more social?

On many sites, streamers and cam models makes use of wishlists, a link somewhere on their profile page that directs viewers to another website (frequently Amazon) with a list of items that they can buy and gift to the streamer. Unlike tips and tokens, where the platform takes a cut, the streamer usually gets to keep the entire value of these gifts herself.

I spend a lot of time looking at these Amazon wishlists during work hours. I have to do this work on a separate computer because my university’s firewall won’t allow me to visit streaming and adult websites, or, it turns out, even forums dedicated to the business of streaming and adult websites. I steal the old computer covered in dinosaur stickers my four year old uses to watch Netflix. Incidentally, his favourite show at the time is Glitter Force (Or SmilyPrettyCure in Japanese), where magical teenagers collect tokens they use to battle evil. Or, as he describes it “you know…the one where the pretty girls turn into love creatures and get money to fight”. I make a post-it on the desktop. My husband reads from it incredulously one morning “black feather whip, animal ears, yoghurt, How to Win Friends and Influence People, Michael Kors clutch…”

The gifts on the Amazon wishlists begin to soft focus until they all look like the same woman. On OnlyFans and Chaturbate there’s a lot of make-up, uncomfortable looking shoes and underwear, headbands with animal ears. And interspersed with these obvious ‘costumes’, there are more pragmatic pieces of active wear, form fitted leggings and sports bras (that feel like they might be worn in the streamer’s down time but which may also be costumes). On Twitch, maybe in a nod to the geekier audience, the wished for items skew more towards quirky gaming and World of Warcraft.

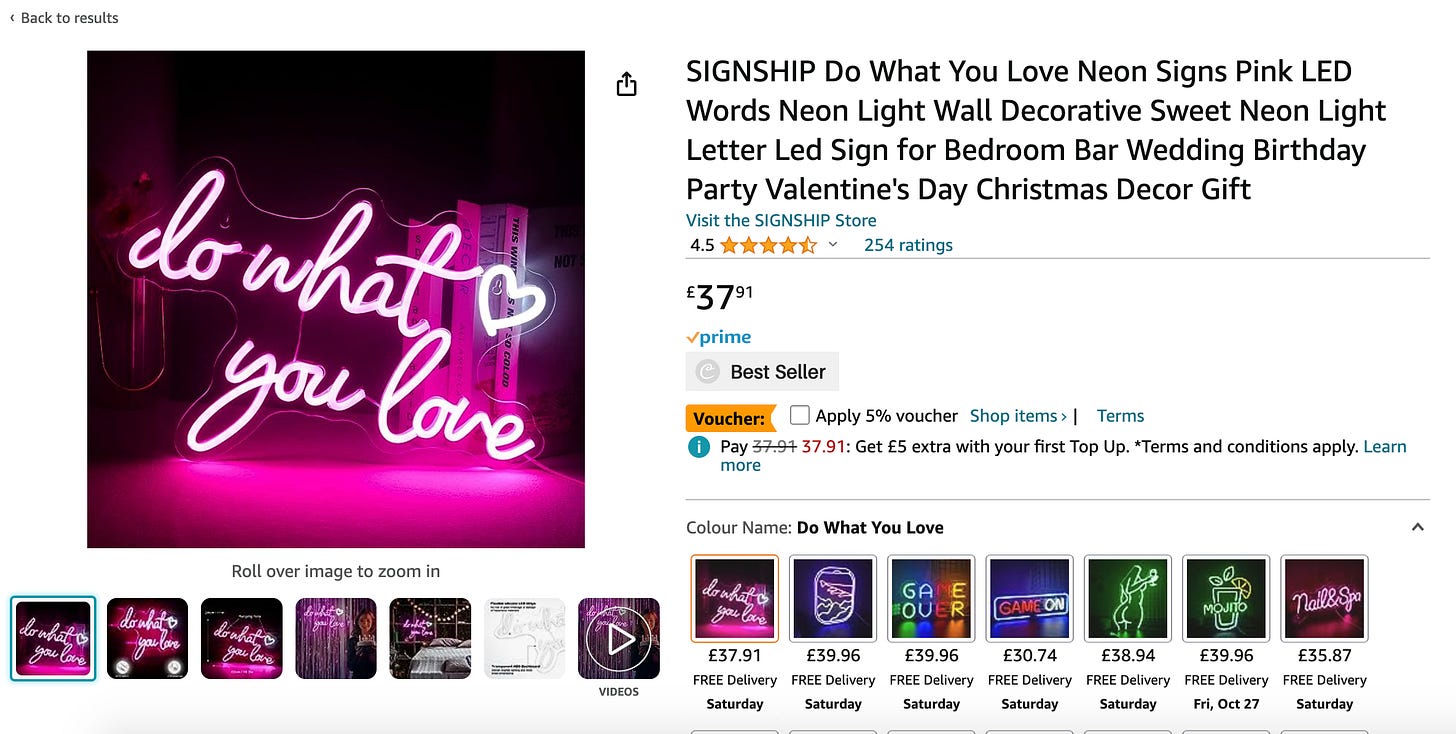

There is quite a bit of home décor, presumably to furnish the streamer’s set, things like throw pillows and strings of LED lights of the kind that you might see strung up in a teenage girl’s bedroom. They are domestic props that feel personal, hinting at, if not exactly a rich interior life, then at least the glimpse of something authentic. But they are also universal enough to have a broad appeal, to feel, like an IKEA showroom, as though a basic set of protocols has been carefully skewed to produce the effect of a real domestic interior - of a real interior life. There’s a dream catcher, a print that says ‘coffee strong, lashes long, hustle on’. One item in particular catches my eye. It’s an LED sign in a dusky pink that says ‘DO WHAT YOU LOVE’ in modern font.

Some wish for the technical equipment designed to light and produce a stage set, like ring lights, tripods, webcam stands. The list of wishes and wants is a mixture of what Erving Goffman called the front and the back stage, although, like the yoga pants, it’s hard to say where the real stuff ends and the performance begins.[iii] Some of the gifts are here because patrons want to buy them (or at least imagine buying them), while others are part of the practical business of producing and editing an online stream.

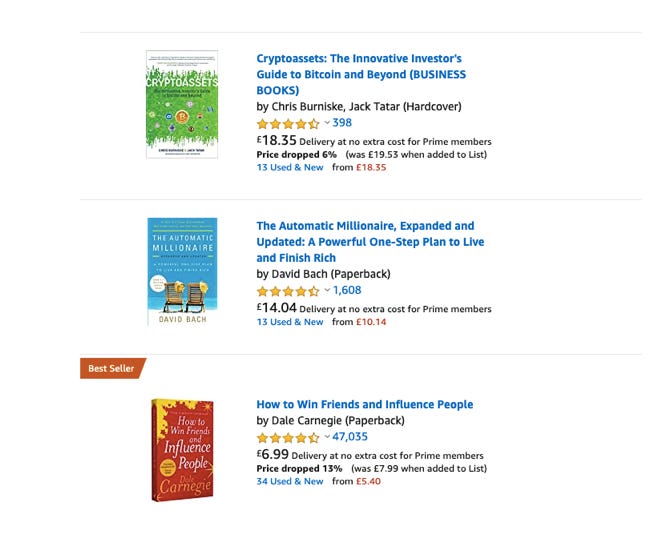

There’s the occasional book; one of my lists from a Chaturbate streamer calling herself Sweet_Ary includes How to Win Friends and Influence People directly underneath The Automatic Millionaire and A Beginner’s Guide to Cryptoassets. Sweet_Ary has also earmarked a Dogecoin mousepad. There are lots of wants and wishes, but very few basic needs. There are lots of cat toys and treats, for example, but only very occasionally children’s clothes or toys.

In my experience, it’s rare to find something that points outside, to the practical business of domestic care and maintenance. I see a cordless vacuum cleaner, but it’s an aspirational Dyson. Once, a jumbo pack of paper towels. But mostly, the items exist in a fantasy world. The business of turning flammable underwear into cash or groceries happens backstage. And then there are the gift cards for popular stores like Amazon, Sephora and Starbucks, picked for their high liquidity.

On message forums, streamers discuss the fine art of Wishlist curation: what is an acceptable gift to ask for? What is too practical? What is too much? What do patrons prefer to buy? What are some good ways of turning the gift into a payment without seeming too mercenary or calculating? What sites are best for selling gift cards at cost? What kinds of privacy issues or potential disclosures does the Wishlist involve – will, for example, their name or home address be inadvertently revealed to the buyer in a receipt? What does it cost to rent a PO box and is it worth it? Oh It is so worth it. There are frequent issues with cancellations and chargebacks that mean the gift balance should be spent or cashed out as quickly as possible, or with patrons marking something as ‘purchased’ for a perk when it really isn’t. There are companies like Wishtender on here, advertising their wares as Wishlist go-betweens – for a fee they allow patrons to experience the gift, but turn it into cash for the streamer at the other end.

Unlike a monetary payment, which is clear cut, and which settles instantly, these gifts have no direct equivalent. Gifting folds the giver and receiver into a lengthier, messier entanglement. It’s not always clear what is being asked for, or exchanged. The contract is implied or unspoken.

These transactions walk the line between markets and online authenticity. Tokens and gifts, as some ‘thing’ that is not quite money, can temporarily shrug off the transaction. But equally, they are part of the work of keeping these things – online work and online play – friendship and business - separate. The gift draws a line between the business of getting paid and the business of ‘doing what you love’.

Bounded Authenticity

“As with other forms of service work” writes Elizabeth Bernstein of sex work, “successful commercial transactions are ones in which the market basis of the exchange serves a crucial delimiting function that can also be temporarily subordinated to the client’s fantasy of authentic interpersonal connection”.[iv] Money can distinguish romance from a sexual transaction but also, if it’s used right, mix up the two, so a fantasy of real connection can be maintained. Lines can be drawn and then blurred.

The same argument can be made of the service of streaming online, where tokens like Bits and gifts like wishlists draw a line between work and pleasure, between markets and the intimate self, between payment, tip and gift. But these gifts also allows the line to be erased. Bernstein calls this fine (im)balance ‘bounded authenticity’, to describe the “numerous ways that clients seek to signal authenticity in their commercial sexual transactions with strippers, including payments through gifts or cocktails (more personal than cash transactions) and their persistent interest in dancer’s real lives and identities”.[v] The numerous ways that sex workers, at one moment engaged in mere surface acting, also take on the work of producing real affect and attachment. Online tokens allow these ties to be forged and cut with dizzying speed.

Bounded authenticity takes place in streaming sites and influencer platforms – any space where the content produced involves a genuine investment in what is framed as the authentic self. Every time we look at a streamer casually eating a bento box in her underwear or an influencer in a baggy grey hoody crying about her mental health, we are witnessing this work, not just as a superficial performance but as a real emotional good. This is real intimacy, but it is also real work - the work that produces the real.

Drawing the Line

In Ireland exposé journalism recently revealed that some prospective female renters have been offered accommodation in exchange for sex. I say ‘revealed’ and yet I think most people already knew this was happening to vulnerable women, just as we know that sex is not for sale but is routinely exchanged for money. Undercover researchers shared recorded conversations and WhatsApp exchanges with prospective landlords offering rooms in exchange for benefits.

We might not know how to draw a hard line between what is inside or outside the market, but we usually know when that line has been crossed. So maybe the question comes down to how much choice we have when we enter into an exchange. What’s at issue isn’t necessarily whether some good is or is not for sale, but if we are witnessing a ‘desperate exchange’. Is the transacting party in a position to say no? Or are they so desperate - for a hit of heroin, or a roof over their head - that ‘choice’ doesn’t really come into the equation?

I think of my nieces, getting ready to go to university for the first time and about the same age as I was in the anecdote at the start of this story. I watch them lip sync with their friends on TikTok. They are so confident. They are so beautiful. Yesterday they got their university place offers, one finger poised over the accept button and another poised to send a draft email requesting a place in Trinity Halls. The cost of accommodation is not an issue. This isn’t a line they will have to walk.

With 12,000 homeless and the cost of an average room in a shared house in Dublin now at €760 a month, more and more of the incoming first years in my college will commute back and forth on lengthy bus journeys, or live strange, protracted half-lives in the city, staying two nights a week in self-catering hotel rooms before returning to other parts of the country. I’ve seen inside some of these rooms during online tutorials, lifeless interiors not unlike a streamer set, somewhere not to live in exactly, but to pass through. When will we draw the line?

[i] Viviana Zelizer. The Social Meaning of Money London: Princeton University Press, 1997.

[ii] Georg Simmel, The Philosophy of Money. London: Routledge, 2004.

[iii] Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life . London: Penguin, 1990.

[iv] Elizabeth Bernstein. "Temporarily Yours." Temporarily Yours. University of Chicago Press, 2021, 127

[v] Bernstein, 103.