On WallStreetBets Elon Musk’s Techno release takes on its own spirit. ‘Don’t doubt Your Vibe (because it’s true)’ is the mantra for self-reliance in the hungry market, for trusting a feeling - perhaps no more than a shiver in your gut - that could be the difference between winning it all and being left holding the bag. Musk is most definitely a vibe. So are Tesla cars.

Vibe – a term straight from the 1960s drop out era, is now part of the remix of counter and business culture perfectly embodied by Silicon Valley on a macro level (and maybe by the fractured family unit of Musk and Grimes and their weirdly named children on a micro level.)

In 1936, Maynard Keynes wrote of the animal spirits that shaped the market in The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, his term for the lurking vibes and contagions that shape consumer confidence. Markets are not just rational systems, Keynes wrote. They are shaped by irrational forces, the animal nature still lurking in the brain stem of homo economicus. Before the idea was applied to markets, animal spirits were already spoken of as a sub-human consciousness - something unknowable, unquantifiable. Something like violence or risk or chaos. Something like a vibe, maybe.

Welcome to the vibe economy.

Day trading became popular during the covid-19 pandemic. This was for a number of reasons: mobile trading apps with zero fees like Robinhood allowed users with little financial experience to dabble in markets. Unlike traditional hedge funds (but very much like most social media applications), these apps have a business model based on user data - not fees. Those who passed the time betting on football, turned instead to retail investing. 2020 also saw the rise of a new brand of influencer on Instagram and TikTok who specialised in dispensing bite-sized investment advice (Mrs Dow Jones on Instagram, TheStockGuy on Twitch, even, arguably, Elon Musk on Twitter). My friend’s seven year old son follows Elon on YouTube “he’s really funny… and handsome’. In an era of growing economic and political uncertainty, Millennials and Gen Zs with precarious employment, in debt and with no chance of financing their futures through so-called ‘legitimate’ channels, were ‘YOLOing’ their rent money for the dream of winning a down payment.

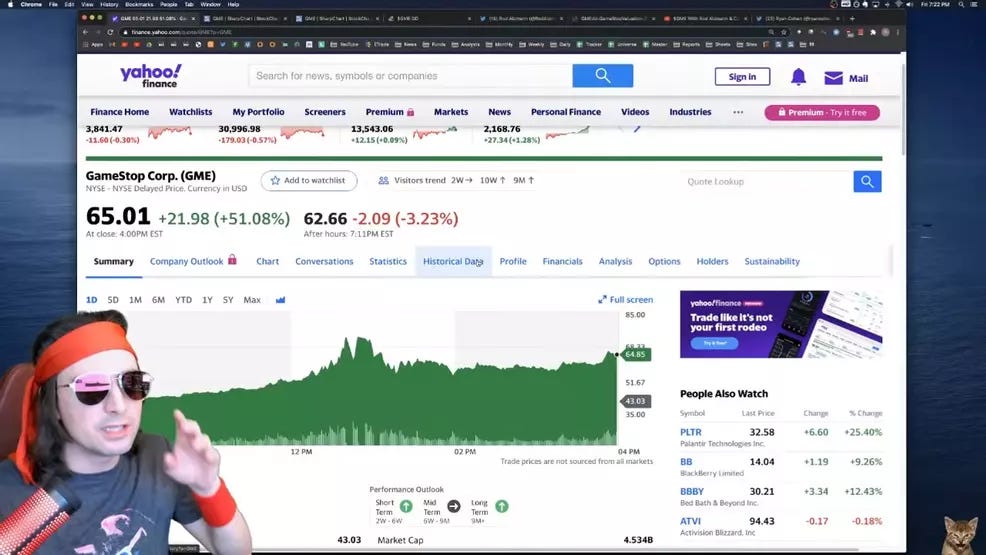

2021 saw a short squeeze driven by a vibe: “Eat the Rich”. A discussion was percolating on a Reddit forum known as r/WallStreetBets about the most commonly shorted stock options. Among them were the nostalgic giants of the digital millennium: Nokia, Blackberry, AMC and GameStop, a bricks and mortar store known for trading in used junk video games. Hedge funds were shorting GameStop, essentially buying a derivative known as a call option that represented a bet on the direction the stock would take. All bets were on Down. Hedge funds were borrowing the stock with the expectation that the price would fall in the future. At this point they would buy it back and recuperate a profit. Led in part by vibes from Keith Gill, (aka Roaring Kitty) on Reddit and other channels (YouTube, TikTok, Twitch), users began a coordinated action to buy and hold GameStop call options (and in some cases GameStop stock) to drive share prices in the other direction, creating what’s known as a ‘short squeeze’. The hedge funds who initiated the squeeze were forced to buy back the stock to avoid losing any more money. GameStop stock went from less than $3 in 2020 to $483 on the morning of January 28th, 2021. At this critical point, the Robinhood app intervened and prevented its users from buying any further call options, citing ‘market volatility’.

If NFTs and GameStop has taught us anything, it’s that it’s now possible to hedge memes in the same way as oil, or real estate, or the life expectancy of a terminally ill patient. These are so called ‘Meme Stocks’. Their value emerges, not from any strong correlation between share price and the underlying asset, but from the hype, circulating around a bet. From vibes. The SEC report on GameStop in October 2021 supports this, concluding that “it was positive sentiment, not the buying-to-cover, that sustained the weeks-long price appreciation of GameStop stock”. The space between illegitimate gambling and legitimate investment narrowed. So did the space between taking an economic stake and posting an unasked for opinion on the internet. Finance apps emerged as a new kind of social media.

The GameStop short squeeze in 2021 and the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank in 2023 were both the result of viral sentiment on social media, which is just another way of saying that they were the result of vibes. A user goes to the bathroom, checks their phone, sees or more accurately feels something they don’t like and decides to move their money. A student with a loan and a Robinhood account watches a video or sees a meme telling him to bet against the failure of Tupperware or Rite Aid despite the performance of the stock. Don’t doubt ur vibe. It was a vast throughput of rumours and transfer requests that traditional risk assessments were not equipped to measure and financial institutions were not built to withstand.

But what exactly is a vibe? A vibe is hard to describe. But that’s the whole point. It isn’t rational. It’s hard to quantify. The vibe is closer to a feeling or an aesthetic. Philosopher Robin James describes it as “a placeholder for an abstract quality that you can’t pin down—an ambience (“a laid-back vibe”). It’s the reason that you like or dislike something or someone (good vibes vs. bad). It’s an intuition with no obvious explanation (“just a vibe I get”).”

TikTok trades in vibes. You are probably drawn to that Pinkydoll livestream because you enjoy the vibe, even though you probably can’t say exactly why. It’s closer, in a way, to the strange kinds of meme coins and emotes and money-like tokens that the internet only half jokily transacts in. This, as Kyle Chayka points out, is what makes the vibe so amenable to social media channels that privilege images, audio and video over texts. TikTok is all vibes and aesthetics, not narratives or political screeds.

What’s maybe most compelling, then, is this shift away from engaging with the internet as a platform for truth or narrative, so much as somewhere that we go for “moments of audiovisual eloquence”, for a vague undefined feeling of rightness, or even profound wrongness. There’s a definite vibe to an image of Trump’s latest electoral campaign, or a tradwife making sandwiches in head to toe cottagecore. Even if it is a #cursed vibe for #cursed times.

We are living in a time where visual culture, and, as a result, populist politics are dictated by vibes. Where a meme of a surprised looking Shibu Inu or a message to apes to HODL can have economic shockwaves, however vague and inconsequential it all may seem.

If Silicon Valley is a counter cultural vibe folded back into the business economy, this has to some extent, always been the model of the culture industries. The cultural economy finds ways to bring vague vibes into the economy and grow rich in the process. Maybe it’s channelling the forlorn vibe of a young Kurt Cobain into Marc Jacobs’ Grunge collection, or the anti-establishment flair of hip-hop and rap music to market Sprite or hacker culture to Club Mate.

This has always been the case in the sale of things like art. Use value isn’t so important. What matters most is vibes.

In the art auction, Jean Baudrillard writes, money (exchange value) gets turned into prestige (sign value). The art auction is unique for Baudrillard because it’s an act of consumption where money (a sign) is exchanged for art (another sign). In this sense, the label ‘art’ is the ideal ideological mechanism – a licence to print your own money. And in this moment of consumption, ‘exchange’ and ‘use’ value are no longer economically correlated. Use value is put out of play. Money is turned into a sign of prestige (a.k.a. a bragging right) that might be wagered in the future for greater financial returns. The sale of art becomes less about the material properties of a work. Its material properties, its location in time and space – these are not so important. What matters more is the degree of information – call it vibes, bragging, hype, buzz, aura, spectacle – that can be generated around it.

During the height of the NFT craze, an arts collective in L.A. called friends with benefit released their own tokens. These tokens conferred not only tokenised art works but also exclusive access to an ‘in’ crowd. Friends with Benefits is not the first example of its kind but it received the most mainstream attention, with over 6,000 members including musicians Azealia Banks and Erykah Badu. It was like a virtual art club – a Soho House for the metaverse. Only, instead of premises, the collective runs on multiple Discord channels dedicated to fashion, music, art, and live-streamed event content. Users must buy into the FWB token to become a member of the collective. Five FWB tokens makes someone a local member, giving them access to the group’s Discord. Global membership costs seventy-five FWB tokens, plus a formal application and interviews with the FWB Host Committee. If membership is approved, this buy-in gives the member access to an NFT gallery and to special ‘token-gated’ events. For the Friends with Benefits DAO, the benefit is in what sociologist Pierre Bourdieu called ‘social capital’ and ‘cultural capital’, to put a name to the economic clout of amorphous connections, good vibes, and good taste. And, like the art auction, the DAO works to seize the floating value of these benefits and turn them into economic capital. Founder Alex Zhang compares the FWB DAO to the merchant class of Venice in Renaissance. Europe (the heads of state were even called doges). With Friends with Benefits, ‘what you’re getting is vibes’, he says: ‘This token is starting to reflect some of the value of those vibes.”

The token traded on vibes. The vibe here is distinctly Burning Man: self-congratulatory counter-culture meets extreme libertarian economic privilege. Like Burning Man, the group also had the ambition to create their own exclusive gatherings. One of these events was a three-day festival in the grounds of Idyllwild Arts Academy, a private boarding school two hours’ drive from Los Angeles. Among the attractions were a digital gallery hosted by OpenSea, a natural wine garden, sound baths with mushroom tea, pool parties, and star-gazing sessions. Anthropologist Kelsie Nabben was among the attendees invited to an intimate acoustic concert by musician James Blake in the middle of a forest. She listened to Blake play the piano and she heard earnest discussions about how to save crypto before the assholes come in and ruin it.

I’m reminded hilariously (painfully) of a Portlandia skit. Beautiful young things attend a Joanna Newsome concert in the middle of a field, stroking each other and playing drums. The shit hits the fan when they have to try and fit her harp in a hatchback on the way home. When Newsome gets upset, things turn ugly. ‘What kind of a vibe is that?’ Joaquim, one of the hippies, wails. ‘What happened to all the beautiful music we did?’’

[0:023 = everybody I slept with in art college]

Buying art can be a way of buying prestige and having prestige can be a way of making money. Friends with Benefits didn’t tokenise art, it tokenised prestige, vibes, bragging rights, membership with the in crowd. It was selling that and people were buying it in the hope that they would belong, but also that they might make money. Kind of like art really.

Robin James describes the vibes economy as one in which speculation is used to turn ‘nonexistent realities’ into a market good. And the tools and techniques used are common to Wall Street and Silicon Valley. They run on vibes. James goes further and argues that vibes/moods/feels are the object of governance in a financialised society, the instruments that connect status laden people to status laden cultural objects. Friends with Benefits is James’ vibes economy in action, the clout of Erykah Badu wired up to a Yerba Mate drink.

During the pandemic, some scholars started to frame the vibe as a way to resist capitalism and burnout culture. During the pandemic, vibing, like raving, was presented as a kind of non-productive space to resist the grindset. “No thoughts just vibes” was yet another vibe. A viral newsletter by Mart Retta called ‘On vibes, the apocalypse and non-linear time’, described it as follows: “It means not doing anything, and yet not doing nothing; refusing a schedule, ignoring your watch, but still filling days with intention, somehow.” If linear time is a product of colonial and capitalist control, Retta argued, vibing could be something else. Breaking away from time measured in units as an economic resource. What could be better? Vibes, after all, are sympathetic resonances. They suggest that even if we live in a shithole, we are feeling the shit together. There is something in this affect that resonates within us all.

In an economy where ambient vibes like Spotify lo-fi beats are marketed as productivity enhancers, where financial capitalism is all about amplifying the content in doing what looks like absolutely nothing, I’m not sure I agree. We Vibin’. It’s true. I just don’t think I trust it.